Drummers, for reasons I’ve never fully fathomed, have historically borne the brunt of rock humour. In Spinal Tap’s back story, they worked their way through 18 tub thumpers, including John “Stumpy” Pepys, who died in a bizarre gardening accident, Eric “Stumpy Joe” Childs, who choked on vomit “of unknown origin”, Peter “James” Bond and Mick Shrimpton, who both expired in bizarre on-stage explosions, and Chris “Poppa” Cadeau, who was eaten by his own pet python, Cleopatra.

Rock drummers are otherwise portrayed as the madcap members of the band, epitomised by Keith Moon “The Loon” and the Muppet he inspired, Animal, and invariably hidden behind a wall of tom-toms and a sea of cymbals of every diameter. Traditionally they are indulged by their bandmates by being provided with time in a live set in which to flail at their skins alone while everyone else disappears to do whatever rock musicians disappear off stage to take care of.

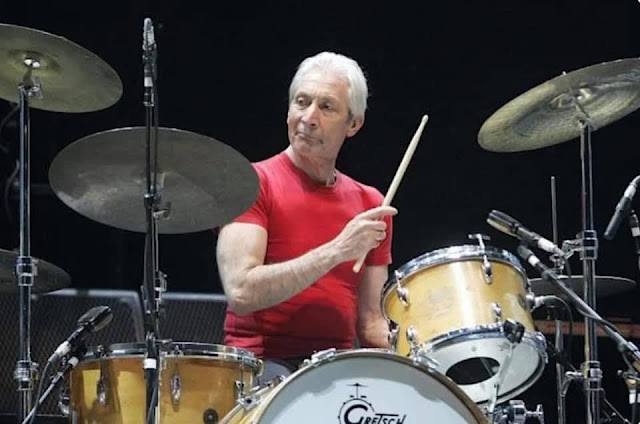

Charlie Watts wasn’t anything like that. He was, by any rock drummer's standards, a modest timekeeper. Resplendent off-stage in Savile Row threads, in contrast to Keith Richards’ ageing pirate look and Mick Jagger’s skinny-jeaned effete, Watts sat behind a simple kit - a single tom-tom, snare, hi-hat, bass and just enough cymbals to punctuate the rhythm only when necessary. Even his drumming style appeared conservative, by comparison to the more expressive likes of Moon, Bonham or Collins. Herein, though, lies the seat of what has allowed the Stones to endure for almost 60 years. Amid the partying, womanising, divorces, dysfunction of every kind (not to mention the Glimmer Twins’ occasional schisms), Watts provided more than just the backbeat. He was the quiet rock of stability, musically, of course, but I suspect also in the more colourful aspects of the outfit that can still justifiably call themselves the “the greatest rock and roll band in the world”.

He was also so much more than - so the somewhat apocryphal tale recounted in Richards’s biography, Life recounts - just “Jagger’s drummer”, too. Part of Watts’ magic was what he brought to the Stones’ music, and part was what he brought to the Stones’ personality. Musically, he was at heart a jazz drummer, but had been drawn into London’s R’n’B scene in the early 1960s, which had its epicentre in the west and south-west London suburbs of Ealing and Richmond. Watts had also worked with the Godfather of British Blues, Alexis Korner. A meeting with Jagger, Richards and Brian Jones in one of those R’n’B clubs led him to joining the fledgling Rolling Stones in 1963, an association that only ended 58 years later with his death, announced earlier this week.

Amazingly, Watts became the first Stone to pass away in old age – at 80 – (with the previous departure only being Jones at the age of 27 through his own misadventure). No one knows quite what has kept Richards going, given the onslaught his constitution has been put under by years of chemical abuse, although the more popular theory is that he has consumed such a sustained cocktail of substances that they have somehow metabolised inside the human laboratory that he surely has become. Watts, by stark contrast – even to the macrobiotic, still-teenage waste-sized Jagger – has always projected a more sober image. Even when he surprisingly succumbed to heroin addiction, it was a brief flirtation rather than a fully-blown descent, and it was ended by Richards’ intervention. Even that dabbling with the darker side of the rock’n’roll lifestyle was conducted with modest privacy. It was, however, a surprising revelation from a musician who, by comparison to the other surviving Stones, had led a decidedly normal life. Watts had been married to the same woman, Shirley, since 1964, and away from the band lived privately on a Devon farm, raising horses, children and grandchildren. Little is known beyond that, as he had always shied away from the attention that the others courted, happy to let his drumming do the talking.

The statement, issued after his death by publicist Bernard Doherty, included the understated phrase “one of the greatest drummers of his generation.” That is the respectful custom on these occasions, but in Watts’ case, thoroughly justified. He applied his jazz chops to the Stones’ blues-infused rock with an intricacy that at times belied the more straightforward rhythmic form of the band in front of him. This stems from his early exposure to Duke Ellington and Charlie Parker records as a teenager before his parents bought him his first drum kit in 1955. This led to regular gigs at the age of 16 in London’s jazz clubs before joining Korner’s Blues Incorporated. In turn, that brought about the fateful encounter with his future Rolling Stones bandmates, though their initial approach to join them was rebuffed as Watts wanted to concentrate on his stable day job at an advertising agency. In fact, even after making his first appearances with the band, he continued to work in a Soho office, up until the point that Decca Records’ Dick Rowe signed the Stones in May 1963 after he’d seen them at the Crawdaddy Club, the legendary crucible of British blues hosted by the old Station Hotel in Richmond-upon-Thames.

Nick Mason, the Pink Floyd drummer, described Watts as “probably the most underrated of all the rock’n’roll drummers”, adding that his natural feel for the music was “just exactly right” and that “no masterclasses or tutorial books, no solos or fancy gymnastics” could ever embellish it. You could say, then, that a drummer knows a drummer. Mick Jagger may have been the Stones’ focal point for most of their 58 years as a performing unit, and Keith Richards the band’s soul, (and, it shouldn’t be forgotten the contributions Brian Jones, Mick Taylor and latterly Ronnie Wood have made to that elixir with their so-called guitar “weaving”), but Watts contributed probably more than most people will appreciate.

So the story goes, Satisfaction was more of a traditional blues drawl before Watts upped its tempo, his crisp snare beat giving the band’s signature song a danceability that ultimately propelled it - which Watts had strongly advocated should be a single against Jagger and Richards’ initial reservation - instantly to No.1 in the UK charts, but more significantly, to the top of the Billboard Hot 100 in the United States, where it remained for four weeks, cementing the foundations of the band’s global dominance for the next five decades. Think, too, of Paint It Black, which opens with an Indian-influenced guitar riff before Watts snapping snare, again, drives the verse. You could argue that this is simply what a drummer is in a rock band for, but the more you analyse Stones songs like these - as well as later hits like Start Me Up or Love Is Strong - and you realise how Watts wasn’t just the Rolling Stones’ drummer but a core component of what made the greatest rock and roll band in the world exactly that and pretty much unassailable in that status.

Watts, of course, would be typically self-effacing about his role. He stoically accepted that the Stones’ colour was provided by the more flamboyant band members, and that just suited him fine. He once famously described being in the band as “five years playing, twenty years hanging around”, but despite the truncation of their current No Filter tour (which began in September 2017 in Hamburg) due to the pandemic, they have remained more active than most other surviving acts of a similar vintage.

The Rolling Stones will continue to roll on. Despite the others’ own advancing ages – Jagger turned 78 last month, Richards will do the same in December, and ‘junior’ Ronnie Wood is 74 – they remain committed to touring and even recording. It remains to be seen how Watts’ death will impact their appetite to continue, though given that they also hold the accolade for remaining one of popular music’s most lucrative operations, the health of the others not withstanding, it would be reasonable to expect that retirement is not in the plan. Bruce Springsteen endured the death of his wingman Clarence Clemons, but Led Zeppelin called an immediate halt after John Bonham’s untimely demise. The Who, it could be argued, were never the same after Keith Moon died before he got old.

It would be gloriously romantic to view the Rolling Stones continued longevity as the result of being inspired by their itinerant blues heroes who played until they dropped, but beyond mercenary need, there is a sense that they will carry on until forces of nature stop them. They will, however, not be the same without their quiet drummer, who kept time but also, passively, kept the order, too.