Views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of any organisation with which the author is associated professionally.

Monday, 12 December 2016

Just because you can, doesn't mean you should

"When Qantas created the 'Kangaroo Route' [from Australia] to London in 1947, it took four days and nine stops. Now it will take just 17 hours from Perth non-stop." So declared, yesterday, the chief executive of Australian airline Qantas while announcing plans to launch the first regular passenger flight directly between Australia and Europe.

Just think about it: 17 hours, probably sat in economy class. Not even in my most slovenly moments of box-set binge-watching could I imagine being able to remain mostly inert, squeezed into an airline seat for the equivalent of how much I'm normally awake during an average day. With four toilets between 232 passangers. Even an upgrade to business class wouldn't make much difference.

Despite my phobia that Australia contains most things that can kill you, it remains a country I would love to visit. But with my occasional flights out to the US West Coast at the very edge of long-haul tolerance (my longest-ever journey - San Francisco to Taipei - was partially aided by an accidental over-prescription of sleeping pills), the only way I could ever manage going Down Under would be by stopping halfway in Dubai or Los Angeles. I know a direct flight would keep the overall trip relatively brief, but I just don't think the risk of DVT, air rage (mine or others') or being sat next to someone with personal hygeine issues for 17 hours is worth shaving half a day off the flying time.

Even the prospect of flying on a Boeing Dreamliner - a plane that actually lives up to its manufacturer's hype and is both more comfortable for the passenger and more economic for the airline - doesn't make the ordeal any easier to contemplate. You'd still feel housebound at 38,000ft, and there are still only so many episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm and Friends you can take.

Labels:

Australia,

Boeing 787,

Dreamliner,

flying,

long-haul,

non-stop,

Perth,

Qantas,

travel

Monday, 5 December 2016

Time still on their side - the Rolling Stones' Blue & Lonesome

Three weeks ago I spent a delightfully indulgent morning in New York City trawling through the 54-year history of the Rolling Stones at Exhibitionism, their own lavish, Bowie Is-style showcase of memorabilia, which had crossed the Atlantic following a successful run in London during the summer.

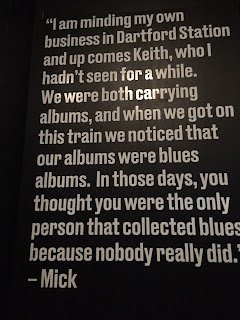

At first it felt odd to be in New York's West Village looking at a history so seeped in London's musical heritage - such as the faithful recreation of the squalid Edith Grove flat shared by Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Brian Jones as The Greatest Rock'n'Roll In The World™ was being formed in 1962. It was in this "pigsty" (Richards' own word) that he and Jagger, his fellow Glimmer Twin, consolidated their love of blues music and, indeed, their enduring - if somewhat tempestuous relationship. That love of the blues had been forged somewhere east of their Chelsea digs, in suburban Dartford where, on October 17, 1961, the former friends from primary school were reacquainted on Platform 2 of the town's station, with Richards sparking up a conversation about the records his future partner-in-crime was holding: Chuck Berry's Rockin’ At The Hops and The Best of Muddy Waters.

Much has been written about how London's middle class suburbs not only succumbed to the music of the Mississippi Delta, but even exported it back there (the Stones famously turning up at Chess Studios in Chicago to record their 12x5 album and discovering Muddy Waters - their hero - up a ladder painting the building's front). While this might sound a little arriviste, the Stones have put back into America everything they took out of it, which is why the choice of Manhattan for Exhibitionism's second run seemed perfectly normal.

Even if the band's roots are firmly in London - in Dartford, Chelsea, the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond that they made their own - they long ago stopped being 'just' a British band. As the recently released tour film ¡Olé! Olé! Olé! depicted, they long ago became a global brand, perfectly at home in Buenas Aires, Caracas or São Paulo, and as much a religion in many of these places as they are rock royalty. One of the points underlined by the film is how, 54 years since their first gig at London's 100 Club, the Stones remain in rude health and still prepared to chart new ground (the film sees them touring Latin America, playing Havana, a rare occurrence for a Western rock band), making you question if any of today's X-Factor crop will be around in five years' time, let alone ten times that period.

The Rolling Stones' endurance, perhaps more so than Paul McCartney, who still tours, is that they are as vital and as invigoratingly entertaining today as a live act, as they ever have been, perhaps more so. They can't need the money, so let's leave that thought at the door, which makes the night-after-night playing of Honky Tonk Woman, Sympathy For The Devil or Satisfaction (and that riff) an endeavour of both consumate professionalism and an enduring love of doing so. Of course, being paid handsomely helps, too: this year they will earn some $65 million from touring alone which, even if you factor in the cost of touring (including wages for non-'full members', like bassist Darryl Jones - who, after 20 years feels he should be an official Stone), will still furnish Jagger, Richards, Charlie Watts and Ronnie Wood's bank accounts handsomely.

Snobs, cynical musos and the jealous might sniff at such business, with all that griping about how these and other heritage tour wrinklies are clogging up channels for younger artists. But the reality is that the world is a better place with the Stones continuing to perform, even if that means the only way of seeing them is to pay inflated ticket prices for vast stadium appearances.

No one would dispute that creatively, their best is behind them, as far back as those louche days of recording Exile On Main Street, Beggars Banquet and Sticky Fingers. But their mastery is undimmed. Richards is still inventing every day, be it chords or tunings, and in many respects is keeping the blues alive as the genre's originals continue to dwindle; Watts remains one of the sharpest drummers in the game, while Wood is a vastly underrated guitarist whose history goes back as long the as peer group of suburban six string-slingers like Clapton, Page and Beck; and Jagger, the ultimate frontman, a paradox of bandy-legged, arm-flailing 28-inch-waisted campness combined with the steely business sense of a corporate CEO.

With Jagger, Richards and Watts in their 70s, and Wood catching up at 69, it is still remarkable that, even with the slick circus around them, the Stones have the energy or the inclination to keep going. But they do, and if anything appear to be doing so with as much relish as ever. Which is why it might be tempting to expect Blue & Lonesome, their new studio album of blues covers, to be a lazy afternoon of bar room standards that any half decent pub band with a Stratocaster-playing lead could knock out. Thankfully, it's not. Instead, it's an accomplished, joyful jaunt through long forgotten songs, reanimating them with the right measure of authenticity, vintage amps and even more vintage guitars, and even Jagger himself demonstrating that, despite the knighthood and executive status, he is still a pure bluesman at heart. His harmonica work throughout Blue & Lonesome is some of the best you'll ever hear.

Recorded over the course of three days last December at British Grove Studios in Chiswick - just a couple of miles from the site of the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond where their residency established the band forever - Blue & Lonesome's 12 songs dig deep into the artists that, as callow teens, the Stones soaked up, from blues harmonica master Little Walter, whose Just Your Fool kicks off the album, to the likes of Howlin' Wolf, Magic Sam and Little Johnny Taylor, whose Everybody Knows About My Good Thing includes a cameo by Eric Clapton, that other veteran from the south-west London blues scene.

Blue & Lonesome is no nostalgic meander, or even an attempt by the Stones to complete a 54-year cycle. This is more than homage, too, no faithful but predictable covers of standards, in the manner of those 'Pays Tribute To...' records K-Tel used to knock out via Woolies.

This is a band aware of their roots, reaching out to enjoy them again, as dynamically as they did in the first place. Then, it was with cheap instruments and an even cheaper home life, but always through the shared love of a music created many thousands of miles away amid the heat, sweat and toil of the American South.

The originals of the form may be all-but gone, but the music is being kept alive by, perhaps, the most famous exponent of the blues, the British band that became a global phenomenon and, six decades later, still are.

At first it felt odd to be in New York's West Village looking at a history so seeped in London's musical heritage - such as the faithful recreation of the squalid Edith Grove flat shared by Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Brian Jones as The Greatest Rock'n'Roll In The World™ was being formed in 1962. It was in this "pigsty" (Richards' own word) that he and Jagger, his fellow Glimmer Twin, consolidated their love of blues music and, indeed, their enduring - if somewhat tempestuous relationship. That love of the blues had been forged somewhere east of their Chelsea digs, in suburban Dartford where, on October 17, 1961, the former friends from primary school were reacquainted on Platform 2 of the town's station, with Richards sparking up a conversation about the records his future partner-in-crime was holding: Chuck Berry's Rockin’ At The Hops and The Best of Muddy Waters.

Even if the band's roots are firmly in London - in Dartford, Chelsea, the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond that they made their own - they long ago stopped being 'just' a British band. As the recently released tour film ¡Olé! Olé! Olé! depicted, they long ago became a global brand, perfectly at home in Buenas Aires, Caracas or São Paulo, and as much a religion in many of these places as they are rock royalty. One of the points underlined by the film is how, 54 years since their first gig at London's 100 Club, the Stones remain in rude health and still prepared to chart new ground (the film sees them touring Latin America, playing Havana, a rare occurrence for a Western rock band), making you question if any of today's X-Factor crop will be around in five years' time, let alone ten times that period.

The Rolling Stones' endurance, perhaps more so than Paul McCartney, who still tours, is that they are as vital and as invigoratingly entertaining today as a live act, as they ever have been, perhaps more so. They can't need the money, so let's leave that thought at the door, which makes the night-after-night playing of Honky Tonk Woman, Sympathy For The Devil or Satisfaction (and that riff) an endeavour of both consumate professionalism and an enduring love of doing so. Of course, being paid handsomely helps, too: this year they will earn some $65 million from touring alone which, even if you factor in the cost of touring (including wages for non-'full members', like bassist Darryl Jones - who, after 20 years feels he should be an official Stone), will still furnish Jagger, Richards, Charlie Watts and Ronnie Wood's bank accounts handsomely.

|

| © Simon Poulter 2016 |

No one would dispute that creatively, their best is behind them, as far back as those louche days of recording Exile On Main Street, Beggars Banquet and Sticky Fingers. But their mastery is undimmed. Richards is still inventing every day, be it chords or tunings, and in many respects is keeping the blues alive as the genre's originals continue to dwindle; Watts remains one of the sharpest drummers in the game, while Wood is a vastly underrated guitarist whose history goes back as long the as peer group of suburban six string-slingers like Clapton, Page and Beck; and Jagger, the ultimate frontman, a paradox of bandy-legged, arm-flailing 28-inch-waisted campness combined with the steely business sense of a corporate CEO.

With Jagger, Richards and Watts in their 70s, and Wood catching up at 69, it is still remarkable that, even with the slick circus around them, the Stones have the energy or the inclination to keep going. But they do, and if anything appear to be doing so with as much relish as ever. Which is why it might be tempting to expect Blue & Lonesome, their new studio album of blues covers, to be a lazy afternoon of bar room standards that any half decent pub band with a Stratocaster-playing lead could knock out. Thankfully, it's not. Instead, it's an accomplished, joyful jaunt through long forgotten songs, reanimating them with the right measure of authenticity, vintage amps and even more vintage guitars, and even Jagger himself demonstrating that, despite the knighthood and executive status, he is still a pure bluesman at heart. His harmonica work throughout Blue & Lonesome is some of the best you'll ever hear.

Recorded over the course of three days last December at British Grove Studios in Chiswick - just a couple of miles from the site of the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond where their residency established the band forever - Blue & Lonesome's 12 songs dig deep into the artists that, as callow teens, the Stones soaked up, from blues harmonica master Little Walter, whose Just Your Fool kicks off the album, to the likes of Howlin' Wolf, Magic Sam and Little Johnny Taylor, whose Everybody Knows About My Good Thing includes a cameo by Eric Clapton, that other veteran from the south-west London blues scene.

|

| © Simon Poulter 2016 |

This is a band aware of their roots, reaching out to enjoy them again, as dynamically as they did in the first place. Then, it was with cheap instruments and an even cheaper home life, but always through the shared love of a music created many thousands of miles away amid the heat, sweat and toil of the American South.

The originals of the form may be all-but gone, but the music is being kept alive by, perhaps, the most famous exponent of the blues, the British band that became a global phenomenon and, six decades later, still are.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)