|

| Picture: Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners |

I have, on this platform, devoted vast quantities of words to the aura of actual rock stars and the impact of their work, rather than their reputation. Heck, I even named this blog and its predecessor after David Bowie. Almost most of this devotion is the result of the visceral enjoyment of music, as unquantifiable and subjective as that is (Stairway To Heaven might grab you by the balls as equally as it might bore another rigid. Bohemian Rhapsody could well be the most exhilarating six minutes of your life, or it could be the most ridiculous). “I know what I like,” is and should be the philosophical approach to any art form. I bristle at any opinion that takes a superior view of one thing over another. It really doesn’t matter if you enjoy it and someone else doesn’t. Good art is supposed to be divisive. Pop music, photography, sculpture, painting - it’s all the subject to the same individual opinion as architecture.

35 years ago Prince Charles drew fire for describing a proposed National Gallery extension as a “monstrous carbuncle” at a speech to the Royal Institute of British Architects on its 150th anniversary, providing further evidence of the prince’s then-growing tendency to speak out on pet peeves. It was at the time considered an audacious attack on modern architecture, especially as Charles was largely at the event to ceremonially doff his titfer to the profession. Instead, he sparked a continuing debate about modernity, leading to inevitable whinges about the legacies that contemporary architects were creating (i.e. anyone veering away from classicism). Notably, Ahrends Burton Koralek’s proposed addition to the National Gallery never materialised.

The reason I bring this up is the death, announced over the weekend, of Richard Rogers - Lord Rogers - part of that triumvirate of rock star architects comprising (Lord) Norman Foster and Renzo Piano who, apart from being great friends and frequent collaborators, made something more out of architecture than simply functional building design. Their work is the creation of monuments to vivid creativity more than merely envisaging rectangular boxes for people to dwell, work in or visit. And yet, collectively and individually, they’ve done more to challenge and enrich contemporary cities than any amount of urban planning. Not always, it must be said, to universal acclaim.

|

| Picture: AEG UK |

Of the Rogers/Piano/Foster trio, I’ve probably experienced more of Rogers’ work than any of the others. Indeed just on Saturday night, as his family were processing news of his death, I was at the O2 Arena in Greenwich watching Squeeze and Madness on stage while ruminating on the incredible structure of what, at first glance, looks like a giant tent.

The Millennium Dome, as it originally was known, was designed by Rogers. It, too, drew the ire of Prince Charles’ aversion to modernism, once calling it a “monstrous blancmange”. Built to celebrate the dawning of the 21st century at a cost of more than £1 billion, it was frequently derided for its cost but also its extravagance as, essentially, a seemingly temporary attraction to celebrate the progress of time by being built in the very place where Greenwich Mean Time was introduced in 1884 (for those who know the area, the Dome/O2 Arena was built on the site of the old Greenwich gas works, at which the father of Squeeze’s Chris Difford worked all his life). But that hasn’t stopped it being one of Europe’s best - and biggest - event venues (and, latterly, a retail centre), which provides a spectacular sight for anyone flying west out of London City Airport, made a memorable appearance in the opening sequence of the Bond film The World Is Not Enough, and several times a week shows up prominently in the EastEnders titles. Some might say Rogers did the job he was brought in for. Even by his standards, however, the Dome was not his most strident creation.

That probably still falls to the Pompidou Centre in Paris, a building that never failed to fascinate me from the outside as much as its inside when I lived in the City of Light and would frequently walk past it on the way to a nearby shopping district. The building, with its exoskeleton of pipes and what looks like permanent construction scaffolding, was to Paris what punk was to classical music. Paris doesn’t really do modernity (the La Défense financial district was punted north-west of the Périphérique ring road for a reason...). So, in the early 1970s when the process began to design a building in honour of former president Georges Pompidou, the eventual design that Rogers and partner Piano came up with was (and, to some extent, remains) as Marmite as it gets.

|

| Picture: Amélie Dupont - Architecte: Richard Rogers & Renzo Piano |

“Bold” doesn’t even cover the dazzling, colourful and distinctly industrial paean to adventurous thinking, which inevitably drew accusations of consecration from conservative Parisians and snobby critics alike. “Paris has its own monster,” wrote Le Figaro, “just like Loch Ness”. Vindication followed after it opened in 1977, becoming one of the city’s most-visited attractions, drawing seven million people in that year alone - the year of punk, it shouldn’t be forgotten - more than the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre combined (and in marked contrast to the art contained therein). The thing with the Pompidou Centre is that once you get past the avant garde exterior, it serves a practical purpose, providing space for art, music performances and a library. How very liberté, égalité, fraternité. We’re back to rectangular boxes again, but with a clear difference.

It’s this combination of the practical and the fanciful that fascinates me about the likes of Rogers. Heathrow’s Terminal 5 and Terminal 4 of Madrid’s Barajas Airport are buildings I have spent plenty of time in, sometimes with the freedom to take it all in, at others in a desperate rush to get from check-in to gate. But on no occasion have I ever felt like I was encased in a box. Indeed, without succumbing to hyperbole, these aviation hubs have more than a sense of wonder about them. This is where the jury of the 2007 Pritzker prize, architecture’s most prestigious award, praised Rogers for his “unique interpretation of the Modern Movement’s fascination with the building as machine,” calling out his transformation of buildings that “had once been elite monuments” like museums “into popular places of social and cultural exchange, woven into the heart of the city.”

Cities are where Rogers made his mark, along with Foster and Piano, whom he regarded as brethren, with a shared vision for high-tech architecture that took cues from machinery and technology more than the shaping of stone. All born in the 1930s, they took their influences from the post-war world, in Rogers’ case the ultra-modern house designs of 1950s Los Angeles, which he visited after graduating from Yale (where he first met Foster). Collectively, they transformed London, New York, Paris, Hong Kong and other cities with a similar outlook. “He is my closest friend, practically my brother," Rogers once said of Piano in a Guardian interview, acknowledging - jokingly - how the Italian behind London’s Shard made him one of “the bad boys.” Foster is another, with his stunning designs for the new Wembley Stadium, Apple’s new space-age HQ in California, and the glass dome addition to the Reichstag in Berlin.

You could argue that architecture stopped being sexy in the 1960s and 1970s, just as rock’n’roll was becoming so. Of course, this is a gross generalisation, just as there was as much naff music in those decades as there was era-defining material. What Rogers and his cohorts achieved, as they got to work on urban skylines in the ’80s and ’90s, was the transformation of ‘boxes in the sky’ into something memorable, fascinating even, something to marvel at before entering, and then on leaving, looking back at and marvelling once more.

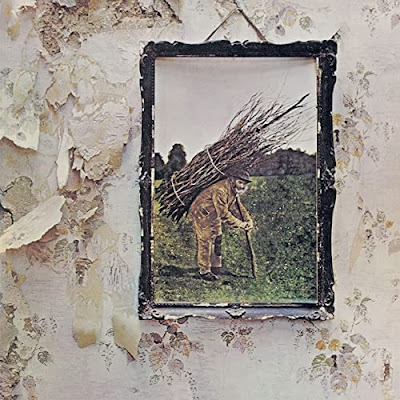

Today, London’s skyline is still the topic of furious debate, as you peer upstream from Tower Bridge at City Hall and The Shard to your left, ‘The Cheesgrater’, ‘Gherkin’ and ‘Walkie Talkie’ (of which Rogers was not a fan) to your right, even if they controversially obscure Christopher Wren’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, one of London’s defining symbols. But one thing you can’t say is that the capital has disappeared “under a welter of ugliness”, as Prince Charles branded modern architecture in a 1984 interview around the same time as his RIBA speech. He also spoke of the “mediocrity of public and commercial buildings, and of housing estates, not to mention the dreariness and heartlessness of so much urban planning”. The irony of Charles’ statement is that these were the very environments that spawned some of rock music’s greatest moments. Transforming them, Rogers - along with Foster and Piano - have injected the sort of progressiveness to architecture that The Beatles, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin and Bowie brought to rock. An enduring legacy, in other words.