1971 was the year that saw the long playing record, in old money, find its place as one of the major artistic mediums, alongside books and cinema. There had been albums before, of course, and ground-breaking ones, too, like Pet Sounds or Sgt. Pepper, that had made ‘album artist’ a thing in its own right. But 1971 generated an unprecedented slew of milestone releases, including David Bowie’s Hunky Dory, The Who’s Who’s Next, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers, Carole King’s Tapestry, Elton John’s Madman Across The Water and at least 20 more that played their part in defining not just the year but the decade itself (for a more comprehensive list and examination of Hepworth’s book, here’s my post from when it was published).

50 years on, one of those albums stands out, arguably more than any of the others: Led Zeppelin’s fourth album. Colloquially known as ‘Led Zeppelin IV’, the officially untitled record could - should, even - be described as a touchpoint for classic rock as a genre. A bold claim, I know, but within its eight distinct tracks, over a run time of 42 minutes and 34 seconds, it remains a remarkable piece of work by a band that, with it, truly hit their stride. Yes, it contains Stairway To Heaven, a song worthy of discussion all on its own, but within its octet of tracks lies a breadth of hard rock (Black Dog, Rock And Roll), ballsy stompers (Misty Mountain Hop) and those rooted in traditional blues (When The Levee Breaks), mystic, 12-string folk (The Battle Of Evermore, Going To California) and pastoral country references. It’s legacy extends well into its 50-year history, too, with John Bonham’s distinct drums - captured by virtue of the cold, damp stairwell of the Hampshire country house they recorded it in (latterly sampled and used by seemingly everyone, including the Beastie Boys and Beyoncé.

“It’s like there was a magical current running through that place [Headley Grange] and that record,” guitarist Jimmy Page recently told Mojo’s Mark Blake. Like it was meant to be. Perhaps this comes somewhat from Page’s singular vision. The former teenage guitar prodigy from Epsom, the third of that remarkable trio of Surrey sons to join The Yardbirds (after Eric Clapton had handed the six string reins to Jeff Beck, who in turn handed them to his friend Page) had largely been the architect of Led Zeppelin, the band renamed from The New Yardbirds in 1968.

Their first three albums had built their profile and credibility on both sides of the Atlantic, riding the post-Beatles wave for British bands with a harder rock tendency in parallel to the early progressive bands that were coming through at the turn of the decade. Notably, Zeppelin built their reputation through, largely, word of mouth and electrifying live performances at events like the Bath Festival Of Blues And Progressive Music and relentless touing in America, playing legendary venues like Bill Graham’s Fillmore East in New York and its counterpart Fillmore West in San Francisco.Notably, too, they had deliberately shied away from releasing singles, the primary promotional vehicle of the pop era. This defiance of convention would remain with Led Zeppelin to the band’s abrupt end in 1980, brought about by Bonham’s untimely death. But in Zeppelin’s fourth album, this belligerence found a particular outlet, led by Page’s own wariness of the way the music industry dictated things, leading to the record being as intentionally enigmatic as the band’s reputational rise had been unconventional.

For a start, the album would go untitled, a notion obliquely referred to in This Is Spinal Tap by the band’s insistence on releasing Smell The Glove with an all-black sleeve and no lettering. While that was a gimmick, Page had another intention: “I didn’t want anyone, including Rolling Stone, making a judgement before they heard the music,” he told Mojo. “I wanted to prove our music wasn’t just selling because of our name.” 37 million album sales may have proven his instincts to be correct, but that wasn’t how Ahmet Ertegun, the legendary boss of Atlantic Records saw it, telling the band it would be “professional suicide” to not even have the band’s name on the cover. “We weren’t backing down,” Page recalls.

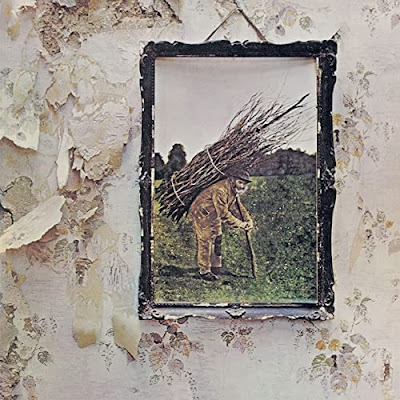

So, for a band that had been feted on both sides of the Atlantic as the Second Coming, Led Zeppelin IV arrived with anonymity, not just lacking cover text, but also photographs of the band anywhere in the album artwork. Instead, the front cover featured a 19th-century agricultural oil painting singer Robert Plant came across in a Reading antiques shop, while the rear featured a drab Birmingham tower block, an attempt to highlight themes of urban and rural living. In place of band pictures, Plant, Page, Bonham or bassist/multi-instrumentalist John Paul Jones. Instead, Page came up with the idea of the quartet being represented by four rune-like symbols. “That whole cover was a Jimmy and Robert production,” Jones has said, somewhat sniffily. “I didn’t quite get it myself.”

Page’s own self-designed symbol, ‘ZoSo’, has itself been a source of much debate, with some pointing to the guitarist’s apparent interest in the work of occultist Aleister Crowley as being its inspiration. Collectively, however, the entire approach of IV’s graphic design is probably just one of those rock band gimmicks which, in 1971, meant that anything went and record company marketeers couldn’t say no. Conventions of album design weren’t broken as few had yet been established. “It’s not something to be questioned or dissected,” Page said of the artwork in his interview with Mojo. “Like the album, it was something that was just meant to be. You listened and made up the pictures in your own mind.”

Which brings me back to Stairway To Heaven, a song commanding a cultural mythology all of its own. As Bohemian Rhapsody is for Queen, Led Zeppelin were so much more than this one song, but Stairway will always be their opus, regarded for it’s sheer expanse and complete defiance of pop tradition. Stairway will also never be regarded as a pop song, but that’s what makes it’s lasting endurance even more extraordinary. It was also, famously, never released anywhere as a single, and yet it has received close to three million plays on American rock radio, according to official figures (it was the most requested song on FM radio stations in the US in the 1970s. By a more contemporary measure, it has been streamed more than 600 million times on Spotify.

To some extent, too, Stairway is the quintessential early ’70s rock album track, and one that - whisper it - comes closer to prog rock than blues-rooted heavy rock. Broken into three sections over its eight minutes, Stairway commences with the pastoral, arpeggiated A-minor chord so beloved of guitar shop wannabes everywhere (remember the “No Stairway To Heaven” sign from Wayne’s World?), rolling into a folkier groove before rocking out in the final third, Page committing an excoriating solo to it with his vintage Telecaster (a Yardbirds gift from Beck). While this structure clearly creates the attention, its lyrics - penned by Plant while, apparently in a bad mood - have been the subject of intense debate. “Depending on what day it is,” Plant once said, “I still interpret the song a different way - and I wrote the lyrics.” The general consensus is that the “lady who's sure all that glitters is gold” is about a woman who accumulates money, only to find out - badly - that life is meaningless and she wouldn’t get into heaven. Beyond that, Stairway is no more profound than the product of a band at the peak of their chutzpah indulging in the early ’70s penchant for album tracks that got a tad widdly-widdly.

Jimmy Page has suggested that when Zeppelin started working on the song in October 1970 it was envisaged as being as long as 15 minutes (still quite brief compared with some examples of the prog genre, such as the 23-minute Supper’s Ready by Genesis), with a construct built on a mystical story that leads to a romping climax. Rumours about hidden satanic messages, contained in reverse-recorded passages, have led to some with too much time on their hands to suggest that Stairway was the Devil’s work. Page’s flirtations with the work of Crowley haven’t helped, either (he did, to be fair, buy Crowley’s house near Loch Ness, which only added to the association). Plant has wisely dismissed the suggestions in pragmatic terms. “There are a lot of people who are making money [out of these suggestions],” he has said. “If that's the way they need to do it, then do it without my lyrics. I cherish them far too much.”

While, though, there is some sense of Stairway being something of a millstone for the surviving members of the band, its place is rock music history hasn’t been lost on them, least of all Page: “I thought Stairway crystallised the essence of the band,” he told Rolling Stone in 1975. “It had everything there and showed the band at its best - as a band, as a unit.” Page called it a milestone for the band, and remains proud that it was never released as a single, a point that only adds to its enigma and its lasting significance. That, though, hasn’t indemnified Stairway from critics (even Plant once said in an interview with Q magazine: “If you absolutely hated Stairway To Heaven, no one can blame you for that because it was so pompous” (he has also branded it a “wedding song”).

Its appearance on Led Zeppelin IV drew no shortage of accusations of being pretentious and bloated. For a song so eulogised now, it wasn’t always so loved by the music press, but then again, they were never the most receptive audience to anything deemed progressive in the early ’70s (although, in my experience, even the most pro-punk/anti-prog journalists all had plenty of art rock in their record collections…).

With John Bonham’s death in 1980 Led Zeppelin came to an abrupt halt. Plant, Page and Jones were persuaded to play at Live Aid five years later, using both Chic drummer Tony Thompson and Plant’s friend Phil Collins on drums (Collins and Page have since traded barbs, with the latter saying the drummer was unrehearsed, and Collins suggesting the guitarist was somewhat out of it on the day. Stairway To Heaven closed the 30-minute set, which also included Rock And Roll and Whole Lotta Love. The song was performed again in 1988 at the Atlantic Records 40th anniversary concert, with Jason Bonham playing drums. The performance wasn’t great, with Plant even managing to forget some of his own lyrics. A better rendition appeared - for the last time - in 2007 when Plant, Page, Jones and Bonham Jr agreed to play at the Ahmet Ertegun tribute at London’s O2 Arena, the final time Led Zeppelin as a band performed on stage. Stairway was a part of Heart’s tribute set in 2012 at the Kennedy Center Honor show, attended by Barack Obama and intended to take a hat off to artists who’d made an important contribution to American culture (the only other British recipients have ever been Cary Grant, Sean Connery and Paul McCartney).

When it was released on Monday, 8 November, 1971 Led Zeppelin IV went to Number 1 in the UK, only narrowly missing out on the top spot in the US. It is still regarded as one of the greatest albums of the classic rock era, and you can take from it what you want in terms of its legacy. It wasn’t Zeppelin’s first and it wasn’t their last, and certainly wasn’t the only memorable entry in 1971’s lengthy parade of classics. But with so much of the music produced that year, it was the work of a group of young men for whom anything went, creatively (though as numerous biographies have revealed, the same could be said of Zeppelin’s touring antics). Unlike today’s somewhat over-curated, packaged pop, it comes from a time when bands had licence to do what they liked, and weren’t dictated to by popular taste or the need to appeal to radio airplay algorithms. Led Zeppelin IV can also be broken down into the individual DNA of the four proponents - the very people depicted by the inner sleeve’s runes - in so far as it draws, in different degrees, from all the different musical interests Plant, Page, Jones and Bonham had at the time - blues, rock, folk, heavy rock and more. “I think that was the beauty of the players, of all of us, that maybe the style went over here, and then over there, and we could cut it wherever,” Plant told Mojo. “But we were in a really fluid creative place.”

That manifests itself in the album’s eight tracks: in Black Dog’s riff; Rock And Roll’s nod to the musical revolution of the 1950s that set everything in train; The Battle Of Evermore hippy-dippyness (enhanced by Sandy Denny’s co-vocals); Stairway To Heaven’s sheer audacity; the bonkers groove of Misty Mountain Hop, Four Sticks’ rhythmic veracity; the wistful beauty of Going To California; and those signature, pounding drums of When The Levee Breaks, which consciously made the genetic link between original Delta Blues and hard rock. 50 years on, what it lacks in the innovations of more revered albums like Sgt. Pepper before it, or The Dark Side Of The Moon which followed two years later, over 42 minutes it remains an utterly compelling album.

These days albums seem designed to be dipped in and out of, with tracks extracted for streaming playlists rather than complete, start-to-finish playback. Led Zeppelin IV, over its eight tracks, defies that. It’s also, by the way, much, much more than that one song that closes Side 1.

No comments:

Post a Comment