There is a bitter irony about laughter being, apparently, "the best medicine". For all its medicinal benefits - boosting the immune system, reducing stress, enhancing resilience, preventing heart disease and so on - it's impossible to ignore how one of the funniest people ever to grace this planet was unable himself to defeat the ravages of human frailty.

That person was Robin Williams, whose death two years ago today is still hard to come to terms with. You would have thought that in this of all years we'd be better equipped: plenty deride online grief - the overwrought posts on Twitter and Facebook for icons never known personally but mourned for as if family members - but in a way, Williams was just that. He was so much a part of our family life.

From his TV debut in Happy Days as the alien Mork (a shark-jumping moment in itself for 1950s Milwaulkee-set sitcom) to its spinoff Mork & Mindy, through his first forays into film (the tragically underated The World According To Garp and Moscow On The Hudson), international audiences were blown away by this human hurricane. God knows what it must have been like to have been starting out in the improv comedy clubs in the late 1970s when this Juilliard-trained, only child of a no-nonsense Ford executive father and a witty, Mississippi-born "Southern belle" mother, unleashed his gift for free-form comedy, one that had been partly shaped making up voices for the enormous collection of toy soldiers he played with as a kid on his own.

Actually, someone who knows what it was like was David Letterman, whom, before his days as America's king of late night chat, saw Williams for the first time as a fellow performer at The Comedy Store in Los Angeles. In his moving tribute to Williams on the first edition of The Late Show after the comedian's death, Letterman recalled: "It's like nothing we had ever seen before, nothing we had ever imagined before. And then he finishes and I thought, 'Oh that's it, they're gonna have to put an end to showbusiness because what could happen after this?' Honest to God, you thought, 'Holy crap, there goes my chance in showbusiness because of this guy''.

Of all the tributes to Williams I've seen and read, Letterman's - unsurprisingly - resonated the warmest, with their 38-year friendship and kindred comic spirit showing through, especially in a compilation tape of the comedian's 50 appearances on Letterman's shows over the years. Summing up those shows Letterman recalled: "One, I didn't have to do anything - all I had to do was sit here and watch the machine, and Two, people would watch. If they knew Robin was on this show the viewership would go up because they wanted to see Robin. And believe me that wasn't true of just television - I believe that was true of the kind of guy he was. People were drawn to him because of this electricity, whatever it was that he radiated that propelled him and powered him."

Like a favourite album you keep returning to, Williams was my go-to guy for laughter. That sounds like trite showbiz billboarding, but it really was that simple. I can - and have - lost entire Sunday afternoons YouTubing Williams' chat show appearances, watching that fervent mind riff volumniously off the tiniest feed. As Letterman said of his own compilation of Williams' Late Show appearances: "It will make you laugh, and really that's what we should take from this - he could make you laugh under any circumstance".

Emotions still expressed two years ago after it was revealed that Williams had committed suicide reflect just how much people held - and still hold - him in their hearts. There were many who expressed anger, branding his suicide as selfish. It was as if the man who'd given us so much - from Mork & Mindy to Aladdin, Good Morning Vietnam to Mrs. Doubtfire, the schmaltzy Patch Adams and Hook, the disturbing One Hour Photo and Insomnia, and the powerful Good Will Hunting, Dead Poets Society and Awakenings - still owed us.

As we now know, there was no more to give. Williams took his own life not as the ultimate act of the sad clown of clické, but as a tragic combination of many debilitating factors. Depression - widely suspected of being the trigger in the wake of financial concerns and his most recent TV show being cancelled - was not the sole cause. "It was not depression that killed Robin," his widow Susan said in one of her first interviews after his death. "Depression was one of let’s call it 50 symptoms, and it was a small one."

Although Williams had a history of health issues, including the cocaine addiction he sobered up from (and forms an essential ingredient of his seminal One Night At The Met show) and surgery in 2009 to correct an irregular heartbeat, he'd been diagnosed with a neurological condition called 'diffuse Lewy body dementia' or DLB, which causes fluctuations in mental status, hallucinations and impairment of motor function. Susan Williams said that the symptoms were worsening ("he was just disintegrating"). The comedian had also been diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease, and this progressive decline had begun to prey heavily on his belief in being able to perform. In his last month, friends had noticed he was become sadder. Susan Williams revealed on American TV, he was well aware he was losing his mind, and then hit a breaking point in July 2014. "It was like the dam broke," she revealed, adding, "If Robin was lucky, he would’ve had maybe three years left. And they would’ve been hard years."

Suicide, she said, had not been foreseen, however. Letterman, in his tribute, said that "more questions are raised than can possibly be answered", by his friend's self-inflicted death "Beyond being a very talented man, and a good friend and a gentleman, I'm sorry, like everybody else, I had no idea that the man was in pain, that the man was suffering".

"Talent" is one of those words that gets showered on performers when they die, but for Williams, it's a word that often got overlooked. As the Oscars and Baftas seem to reflect, comedy is not always an easy attribute to reward. If someone's funny, and they make us laugh, we settle for that without demanding anything else. It's a simple emotional response that doesn't need over-examination. But if you watch Williams on a chat show or clearly deviating off-script with his wildly inventive improv in Good Morning Vietnam, it was profoundly obvious just what a unique talent he was. Where it came from - if it had a distinct origin or evolved - is hard to say.

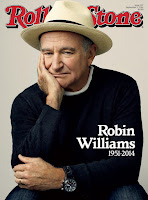

"There's a kind of loneliness to all comedians, but there was a certain sort of solitude in him that I didn't see in a lot of people," was an interesting remark given to Rolling Stone magazine's Willams tribute issue by his friend David Steinberg. Perhaps some of this had to do with being an only child. His Paradise Cay home, where he died, is in the same secluded peninsular across the bay from San Francisco that his family had moved to when Williams was a teenager. Even after Juilliard he returned straight back to California.

Many have cited his unnanounced appearances at improv clubs as a basic craving of attention. Those close to him, however, say it wasn't attention he craved but feedback. And despite TV appearances to the contrary, he wasn't always 'on': "People think they know you," he said in an interview once. "They expect you to be literally like you are on TV or in the movies, bouncing off the walls. A woman in an airport once said to me, 'Be zany!'. People always want zany, goofy shit from me. It takes a lot of energy to do that. If you do that all the time, you'll burn out".

His release was cycling. Having sobered up from cocaine addiction ("God's way of telling you that you've got too much money) and alcoholism ("It escalated so quickly - within a week I was buying so many bottles I sounded like a wind chime walking down the street") Williams channeled his addictive personality into buying bicycles (at his death he owned 50) and riding them around the glorious Marin County headlands near his home, or in Tuscany with friends. Cycling was, he once explained, "an escape - a safe place to get away from it all".

His release was cycling. Having sobered up from cocaine addiction ("God's way of telling you that you've got too much money) and alcoholism ("It escalated so quickly - within a week I was buying so many bottles I sounded like a wind chime walking down the street") Williams channeled his addictive personality into buying bicycles (at his death he owned 50) and riding them around the glorious Marin County headlands near his home, or in Tuscany with friends. Cycling was, he once explained, "an escape - a safe place to get away from it all".

"My battles with addiction definitely shaped how I am now," Williams said another time. "They really made me deeply appreciate human contact. And the value of friends and family, how precious that is". He was married three times - the first to waitress Valerie Velardi whom he'd met pre-fame in San Francisco, the second to his family nanny, Marsha Garces, in 1989, and the third to graphic designer Susan Schneider in 2009 after they'd met in an Apple Store. His three children - son Zak, from his first marriage (and another key reference point in the Live At The Met show), and daughter Zelda and youngest son Cody from his second - kept him grounded. Family life appeared to replicate the family ideal Williams projected in some of his cuddlier films, and played a profound part in protecting Williams from those traits which threatened to unravel him.

In one of the most moving tributes, Williams' friend, the comedian Bobcat Goldthwait, who wrote and directed the actor in the ironic anti-family comedy World's Greatest Dad, quoted one of his character's lines in an interview with Katie Couric on Yahoo! TV: "'I used to think the worst thing in life was to end up all alone. It's not. The worst thing in life is ending up with people who make you feel all alone.' [Robin] wasn't, he was surrounded by a wonderful family.”

In the end, though, not even the strength of family life could indemnify Robin Williams from his physical debilitation. His suicide may, still, not be agreeable or acceptable to some. But perhaps we have, two years on, a better understanding of the creeping, cumulative despair that led him to it. Perhaps, too, we're being the selfish ones, wishing that, to quote Terry Gilliam - "the most unique mind on the planet", the comic genius behind Mork, Adrian Cronauer, Euphegenia Doubtfire, Aladdin and thousands of chat show and comedy club riffs could keep turning. Sadly, it could not.

No comments:

Post a Comment