Just beyond the eastern extreme of California’s Yosemite National Park, not far from the border with Nevada, sits Mono Lake, a salty body of water formed three-quarters of a million years ago. I came across it considerably more recently than that - 1992 to be exact - but at the time had no appreciation of the cameo it had made in my musical adolescence when I stopped there for what Americans politely term a “comfort break”.

For context, I was midway through a month-long tour of the American West, albeit in December when the tourist hordes are elsewhere. Having driven from Los Angeles up the Pacific Coast Highway to San Francisco, and then north-east to snowed-in Lake Tahoe, I was heading south towards Death Valley along the scenic Highway 395, with California’s spinal Sierra Nevada mountains to my right. Just south-east of Yosemite, I came across Mono Lake and its seemingly abandoned visitor centre. Making use of its facilities, I then took in a view of the lake’s eerie stillness, framed by unique tufa formations. It would be another 25 years - and several visits further to that part of California - before I’d come to realise where I’d seen that tufa before. On a display wall at London’s V&A museum, as part of the Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains exhibition, was a blow-up of the inner sleeve of the band’s ninth studio album, Wish You Were Here, depicting a perpendicular diver performing a handstand in, yes, Mono Lake.

The image was the idea of Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell, the photographer and co-founder with Storm Thorgerson of the Hipgnosis design studio which, from the end of the 60s to the beginning of the 80s produced some of the most distinctive album covers ever committed to 12 inches-square of cardboard. Over 15 years, they produced more than 250 sleeves for artists as varied as Led Zeppelin, Paul McCartney, Humble Pie, 10cc, Leo Sayer, Genesis, ELO, Black Sabbath, Olivia Newton-John and XTC, as well as Pink Floyd, with whom they became most closely associated.

It’s the perfect subject, then, for Us And Them: The Authorised Story Of Hipgnosis, a new book by journalist Mark Blake, whose previous work includes arguably the definitive Floyd account, Pigs Might Fly. “I’d always been quite interested in the idea of doing a book about Hipgnosis,” Mark declares. “I’d interviewed a lot of their associates for Pigs Might Fly - particularly the people who were around at the beginning of their work, their contemporaries, their friends from Cambridge and London in the early days.” A book about the creative duo was a natural next step, especially as Mark had come to know Powell and, in the later years of his life, Thorgerson, in particular, working on the very V&A exhibition I’d been to see.Hipgnosis and Pink Floyd’s histories are intertwined: Thorgerson and Powell had been cohorts of the band’s founder members, Syd Barrett and Roger Waters, in Cambridge before they all migrated to London to attend universities. There they met Nick Mason and Rick Wright, eventually becoming fixtures of the capital’s underground music scene as ‘The Pink Floyd Sound’.

A year after Pink Floyd - as they became - released their debut album, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn in 1967, Thorgerson and Powell established their working relationship with the band. “Storm was attending the Royal College Of Art, studying film, and Po got a job designing sets for the BBC,” says Mark. “Then Po got sacked and fell into low levels of criminal activity - bank fraud, stealing cars and so on. He got into an awful lot of trouble. It was then that they decided to talk Pink Floyd into letting them design the sleeve for their second album, A Saucerful Of Secrets.” Released in 1968, and made amidst the deteriorating mental health of Barrett (whose departure midway through recording led to David Gilmour joining the group), the album was only the second time that label EMI had allowed an artist to use designers from outside their own in-house art desk. Thorgerson and Powell took it as an opportunity to exploit the changing nature of record covers.

“Much of their success can be traced to that of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” says Mark, referring to the grandaddy of progressive rock and its ambitious pop art sleeve designed in 1967 by Peter Blake and Jann Haworth. That landmark inspired a decade of graphic design in rock which saw Hipgnosis, as well as their equally conceptual contemporary Roger Dean, taking cover art into new realms of creativity and expression. Prog bands like Pink Floyd, Yes and Genesis became fertile muses for such designers, turning cover art into an integral component of the narrative their records pursued, invariably conveying dioramic third dimensions through fantastical, somewhat lyrical and always unique imagery.

For Thorgerson and Powell, getting their concepts across the line with some bands often owed more to the force of personality than creativity alone. “There was one slightly oddball character in Storm, and the slightly more measured character in the shape of Po,” Nick Mason tells Mark in the book. “And it stayed that way for the next fifty years.”

|

| Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell |

As their reputation grew, from 1968 and into the new decade, Hipgnosis became particularly prevalent working for artists sat on various degrees of the progressive spectrum, producing sleeves for myriad acts like Humble Pie, Emerson Lake & Palmer, Rory Gallagher, T-Rex, Wishbone Ash (for their album Argus, with its seminal cover) and even Syd Barrett, for his haphazard but still loved post-Floyd solo albums. At the same time, the relationship with Pink Floyd continued to bear fruit, with covers for the albums More, Ummagumma, Atom Heart Mother, Meddle and Obscured By Clouds.

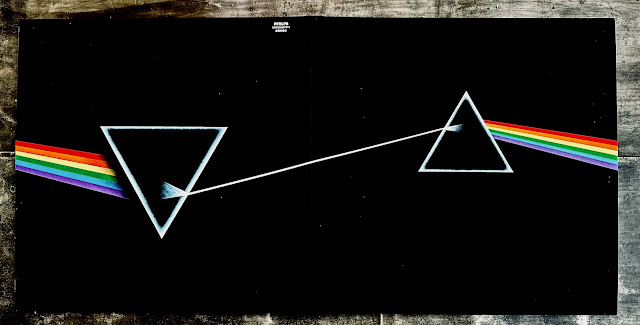

However, the album that still defines the Hipgnosis legacy - and possibly the entire genre of LP art - came in March 1973: The Dark Side Of The Moon. Thorgerson and Powell’s brief from Pink Floyd was to produce something uncomplicated, a contrarian response to opinions amongst the suits at EMI that their previous sleeves for the band had been belligerently obscure and even unmarketable. What they came up with - with a little help from a school book - was the now singular black cover with its beam of light dissipating through a prism into a spectral rainbow.

“I don’t think there was so much foresight and forward thinking in it,” says Mark Blake. “A lot of the time it’s ‘We’ve got to get a cover out - there’s a deadline looming!’. The band wanted something simple so Storm and Po found the prism design in a physics textbook and ripped it off, getting their illustrator George Hardie to create a beautiful design.” To make up for the spartan outer cover, Hipgnosis included some visual extras. “You got the poster of The Great Pyramid and a load of stickers,” says Mark. ”That was Storm trying to shoehorn some bigger ideas in.”

Nowhere on the front or back was there any mention of Pink Floyd or the album’s name. Though not the intention, it reflected an undercurrent of growing distraction within the band (Roger Waters has, with customary misery, described Dark Side as “the beginning of the end”), and the lyrical themes of greed, fame, mortality and even the mental decline of their founder Barrett. Wrapped in a package not dissimilar to a box of Black Magic chocolates, The Dark Side Of The Moon became the standout release of 1973, a year which saw records like Bowie’s Aladdin Sane, Led Zeppelin’s Houses Of The Holy (with a cover also designed by Hipgnosis), Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells and Bruce Springsteen’s Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ amongst its pantheon.

Mark acknowledges Dark Side’s enduring success but doesn’t attribute it entirely to the legendary artwork: “I don’t think that it is just down to having the boldness of not having the band’s name anywhere on the cover. I know it wasn’t the first time Storm and Po had done that with Pink Floyd or, in fact, another band.” Music, he says, has clearly been the album’s defining character, but over time the cover has contributed to the record’s legend, albeit contentiously for Hipgnosis: “I think they got paid about 500 quid all-in for that. Years later, Storm tried to get more money out of Pink Floyd because he believed that the cover had contributed more to the sales.”

To date The Dark Side Of The Moon has sold more than 45 million copies worldwide - and continues to do so, even reaching new audiences. My 18-year-old step-daughter asked for a vinyl copy for Christmas two years ago, and even this last December the LP was selling steadily when I visited Fopp! in Covent Garden. While it contains some of the Floyd’s most revered music - Breathe, Money, Time, Us And Them, The Great Gig In The Sky et al - that cover art has found itself peppered throughout the zeitgeist of the last 50 years. “I think both Storm and Po had a complicated relationship with Dark Side,” says Mark. “It’s not their favourite work, but it is their most famous work. It’s a very simple design but doesn’t have the narrative quality that Wish You Were Here had a couple of years later, which I think was certainly one of Storm’s favourite Floyd covers.”

That record, released in 1975 as a follow up to Dark Side, came with a significantly larger production budget for Hipgnosis, which is how Powell ended up in California for three weeks, an entourage in tow, taking the Mono Lake shot. At the same time, he captured the faceless bowler-hatted man for the back cover (shot in the Mojave Desert), and the front cover image of businessmen shaking hands on a Hollywood backlot, with one of the two stuntmen used for the picture actually on fire - a stunt that almost went very badly wrong.

The story of Hipgnosis isn’t, however, exclusively the Pink Floyd Story. Their work for other artists was equally as distinct, and sometimes just as complicated, though Mark feels they never came up with anything as singularly impactful as The Dark Side Of The Moon. “They became the hip guys to go to after Dark Side and Houses Of The Holy, and also, weirdly, Wishbone Ash’s Argus. That was the album Jimmy Page saw in a record shop: when I interviewed him for the book, he told me ‘I saw this album with a Viking on the cover. I never listened to it but I liked the cover.’ So he rang up Storm and said, ‘Come and do our next album’ [for Led Zeppelin]. After that they got the call from Paul McCartney, who asked them to do Wings’ Band On The Run.” That cover, Mark says, was entirely McCartney’s idea, and famously featured a Clive Arrowsmith picture of Paul and Linda McCartney, Denny Laine, Michael Parkinson, Kenny Lynch, James Coburn, Clement Freud, Christopher Lee and John Conteh posing against a wall, illuminated by a prison searchlight. Still, it had a domino effect, bringing many more bands to Thorgerson and Powell’s door.

Genesis was another band that enjoyed a run of distinctive Hipgnosis-designed covers, commencing with 1974’s The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway - Peter Gabriel’s final work as lead singer and a concept album about a Gulliver-like Puerto Rican street tough descending into the New York underworld. Its literal cover - including a new band logo - was peak Hipgnosis. “Storm was incredibly principled about certain things,” Mark explains. “He would go to the ends of the Earth and spend his own money on getting a cover right. There were certain ideas he wanted to do for bands that they rejected because they wouldn’t have been able to afford it. Storm would do it anyway, just because he wanted to. But by the same token, if Pink Floyd turned an idea down, he’d have no hesitation in trying to fob it off on another band.”

10cc and Genesis were, in particular, beneficiaries of Thorgerson’s ‘generosity’: “The cover of 10cc’s Bloody Tourists is actually a picture of Powell with a map across his face in the West Indies. They pitched that to Genesis for …And Then There Were Three, with the idea that they’d just lost Steve Hackett [who’d quit the band in 1977] and they’re now looking for a new direction.” Genesis, Mark says, weren’t having it, so Hipgnosis took the concept to 10cc who did.

Peter Gabriel recounted a similar experience to Mark for his first three solo albums, which had Hipgnosis covers. Every time he met Thorgerson, he’d be told: “I’ve got a great idea for you, Peter,” to which Gabriel would say: “You’ve fucking tried that on Led Zeppelin, haven't you?”. Mark reveals: “Storm would reply: ‘Yes, but it's perfect for you!’ So, there’s this sort of reject pile that Gabriel would always be confronted by. With Storm it was a weird mix of being incredibly principled and that art is everything, to ‘just have this’.” The covers Gabriel eventually agreed to were markedly different to those Hipgnosis produced for his old band and their contemporaries. While still surreal, they featured distorted images of the singer himself, but to his American record company’s frustration, Gabriel was naming his albums simply ‘Peter Gabriel’, with their covers the only means of distinguishing them. Eventually, the American label would remarket them respectively as ‘Car’, ‘Scratch’ and ‘Melt’, based on the Hipgnosis imagery, just to help the hard of thinking.

If Sgt. Pepper changed the nature of album covers, the early 1980s brought two shifts in the medium itself with industrial developments that, indirectly, altered Thorgerson and Powell’s trajectories. In 1982 Philips and Sony heralded the digital music age by introducing the Compact Disc. The 12-inch canvas that Hipgnosis had made their own became increasingly redundant. Until Gen Z’ers discovered their parents and grandparents’ vinyl collections - and a new romance began with cover art, appearing on bedroom walls and irony-nodding T-shirts - the designs that stood tall in my teenage years became minimised to fit 12cm ‘jewel cases’. Later still, with the advent of streaming, cover art would be minimised further to fit the postage stamp-sized screen real estate of online services.

|

| Mark Blake |

The arrival of MTV in 1983 was the next industrial change, providing Hipgnosis with a new outlet: “All the money that might have once gone into sending them to the Sahara Desert to photograph footballs in the sand for a cover was now being spent on videos,” says Mark. “So that’s why they wound up the company and decided make music videos, which they did for a few years quite successfully…until it wasn’t.”

While one of their first forays was the clip for Paul Young’s Wherever I Lay My Hat, the video age brought Hipgnosis back into contact with some of their older clients, who were finding new fans through the medium. “They did stuff for Robert Plant and Jimmy Page’s bands,” says Mark. “Owner Of A Lonely Heart [the hit single that revived the fortunes of Yes] was another big one for Hipgnosis. They got in on the ground floor with these older bands trying to relaunch themselves and having to make videos. And obviously, the bands went to the very guys who’d made their album covers, because they figured that they’d feel comfortable with them.”

Although Hipgnosis, as an entity, was wound up in 1983, there is a coda to their greatest legacy in designing covers for LPs. Vinyl sales grew for the 15th consecutive year in the UK in 2022, reaching close to 5.5 million - the highest growth since 1990. What began as baby boomers looking to reconnect with their long-discarded copies of classic Beatles and Bowie records has been boosted by the record-selling phenomenon that is Taylor Swift, as teenagers, moving on from raiding their elders’ records, have adopted their own heroine in the Nashville star. Visit any record shop - from independents to the few remaining chains - and a miasma of album covers will greet you.

So, is Mark Blake’s celebration of arguably the greatest purveyors of album art perfectly timed? Not necessarily, he says: ”The 50th anniversary Dark Side Of The Moon was the main reason for writing the book. The thing about [the resurgence of] vinyl is interesting, though. I’ve got a 17-year-old son, and when he was first looking through my old records, he said to me, ’Some of these covers would look great if you had them framed on the wall,’ which I think is quite interesting. He listened to Dark Side a couple of years ago, because he’d heard a lot about it - and probably because of the cover.” The vinyl upswing does help, says Mark: “It shows there’s an interest in it as a format, but I don’t think there would have been interest in [a book] ten years ago. We’re moving on to a time where people maybe are reassessing some of this stuff a bit more now, especially after the Pink Floyd exhibition at the V&A. It just feels a bit more timely now.”

Us And Them: The Authorised Story Of Hipgnosis by Mark Blake is published on 2 February by Nine Eight Books

No comments:

Post a Comment